Remember when music production felt simpler? Before the dizzying array of plugins, YouTube tutorials, granular synthesis, spectral processing and all that time searching for the perfect hi-hat. As magical and helpful as all these things can be, some producers across the globe are going DAWless. They’re ditching the digital audio workspaces (DAWs) for instruments and hardware to focus solely on, as Hans Zimmer puts it, the “core pulse” of their scores.

Whilst DAWs like Ableton, Logic, Fruity Loops and Garage Band have democratised music production and given us some of the universe’s most beloved songs, there’s an ever-growing DAWless movement to create music that feels less contrived, more authentic, improvised and most importantly, alive.

Why are so many producers captivated by the often expensive hardware, the confusing cable management and glitchy sound of modular analog synths? And who are the key people in its resurgence?

Origins of analog

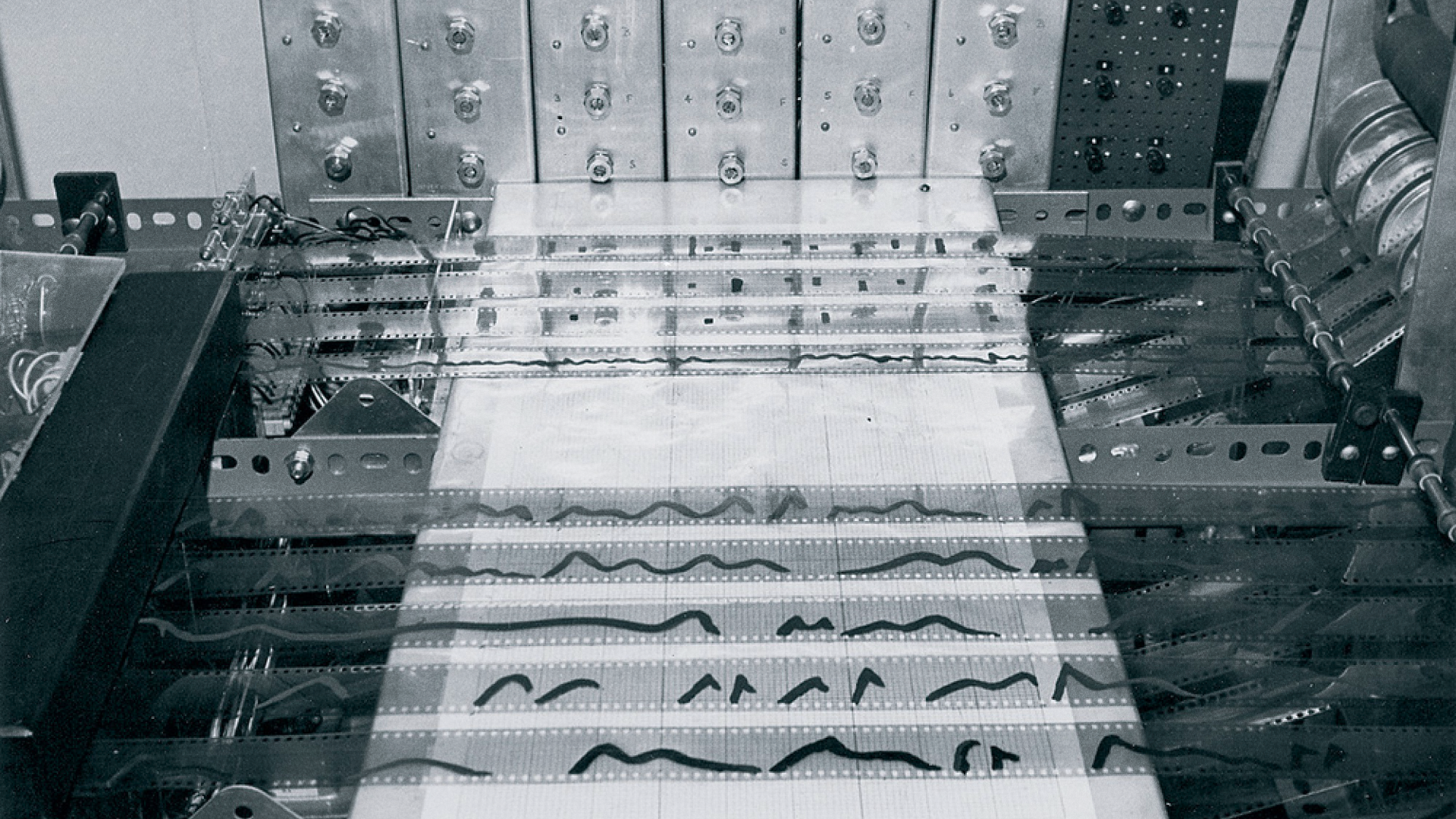

In the early 1960s, two men working 3,000 miles apart simultaneously invented the modern synthesizer. They approached it with completely different philosophies, creating the ‘East Coast vs. West Coast’ divide that still exists in DAWless circles today.

Robert Moog wanted to create an instrument for keyboardists. In 1964, he debuted his first modular system components at the Audio Engineering Society Convention. At one of these conventions he met Mort Garson (pictured above) who became one of the first arrangers and composers to work with the early synthesizers.

Don Buchla, on the other hand, hated the piano keyboard, calling it a “dictatorship of 12 notes.” He created a different system altogether, connecting touch plates and sequencers to generate sounds that were alien and rhythmic. In 1963, Buchla received a grant to build the Buchla 100 series for the San Francisco Tape Music Center.

By 1970, the industry realized that modular systems (with their literal miles of cables) were too complex for the average touring musician. So, Moog released the Minimoog Model D, arguably the most important synthesizer ever made. It took the most popular modules from the Moog systems and hard-wired them into a portable wooden case, giving the keyboardist the power to play lead solos that could compete with a guitarist’s volume and expression.

Technological innovation

Minimoog’s biggest rival at the time was The ARP 2600. Created by Alan R. Pearlman, this “semi-modular” synth didn’t require cables to make sound, but you could use them to override the internal paths. The voice of R2-D2 in Star Wars was created using an ARP 2600.

Up until 1977, almost all synthesizers were monophonic (they could only play one note at a time). But then came the Yamaha CS-80. A massive, 90kg beast that allowed for 8-note polyphony. It is the sound of Vangelis’ Blade Runner soundtrack. A year later, The Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 changed the game with patch memory. For the first time, a musician could save their sound and recall it instantly with a button, rather than spending 20 minutes re-patching cables.

By the end of the 1970s and into the early 1980s, these now coveted pieces of hardware were ubiquitous in high-end studios and were being used to create classics like Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love,’ Gary Newman’s ‘Cars’ and Soft Cell’s ‘Tainted Love.’ The 1980s saw a digital revolution in electronic sound production with more stability and presets, but at the cost of ‘menu diving’ which saw people spending much time looking for sounds rather than creating them. It was also the decade which saw dance music’s most important developments: the Roland 808 and 909 drum sequencers.

Released in 1980 and 1983 respectively for around $1100, both were commercial failures because competitors like the LinnDrum offered more realistic sounds. Production ceased after a few years, with roughly 10000-12000 units manufactured for reach.

The rise of accessibility

As prices dropped in the late 1980s, it was adopted by pioneering artists who made use of the ability to use samples as sounds. Today, original 909s are highly sought after, with prices often exceeding $3000, and its signature sound has been heavily emulated by both Roland and third-party software. Without these machines, Techno, Acid House and therefore every electronic dance movement after it would’ve sounded different. One group of 909 fans in the Netherlands even started a whole festival in 2011 as homage to the pivotal 909.

In 1991, Digidesign created ProTools, which allowed for four tracks of digital audio and MIDI. It wasn’t just software; it required expensive external hardware (DSP cards) to do the ‘heavy lifting’ because computers back then were too weak to process audio on their own. But it became the industry standard for professional studios, eventually moving the entire recording industry away from tape.

And so began the DAW dominance of the next 35 years.

The DAW days

Without DAWs, we’d never have Burial’s Untrue, Skrillex’s Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites or Grimes’ Visions. Probably every record you can think of since the 1990s, has been processed using a DAW. But that’s potentially the problem.

Despite there being thousands of different plugins and ways to record sound with instruments, there is a danger that all music starts to sound the same. A 2012 study published in Scientific Reports by Joan Serrà analyzed a dataset of nearly 500,000 songs released between 1955 and 2010, focusing on pitch, timbre and loudness. They found that the “timbral palette” – the variety of textures and instrument sounds – has shrunk. Essentially, producers are using the same types of sounds over and over again.

One of the large reasons they might be using the same sounds is because you could spend a whole lifetime searching for a particular kick drum that sounds right as Jack White said in this interview with Liam Riordan: “It’s very easy to keep clicking and clicking and fixing and fixing [in a DAW]. Whereas, if you put it onto tape… that’s it. That got rid of, whatever, fifty percent of the choices immediately”, said Jack.

The decline of musical diversity

Despite the mass-musical explosion that is the last 20 years, the diversity of transitions between chord combinations has diminished. Music became more “predictable” in its movement. With everyone using the same Splice sample packs, the acoustic “DNA” of songs began to homogenise.

A key theme in DAWless culture is the rejection of the ‘piano roll’ and ‘quantization.’ In a DAW, notes are placed on a beat grid. This removes the subtle human ‘swing’ (the milliseconds of being behind or ahead of the beat) that defines genres like Jazz, Funk or early Motown. Legendary beatmaker J Dilla was known not to quantize his beats, which made his beats feel natural and human made with their wonky time signatures.

A study by Hargreaves and North (1997) and later research into ‘acoustic richness’ suggests that when music becomes perfectly rhythmic and ‘on the grid,’ it becomes easier for the brain to process but less ‘stimulating’ over long periods. This leads to a “standardized” sound where everything feels mechanically identical.

If I tried to pinpoint a defining moment when the analog movement really began to make tracks that entered the modern producer psyche, I would likely fail. There are so many key individuals and factors at play. But to see why the DAWless movement began to make sense, we need only look at the Billboard Top 10 for the year 2010.

Billboard’s Top 10 in 2010

- Kesha – ‘Tik Tok’ (Prod. Dr. Luke, Benny Blanco)

- Lady Antebellum – ‘Need You Now’ (Prod. Paul Worley)

- Train – ‘Hey, Soul Sister’ (Prod. Espionage)

- Katy Perry (ft. Snoop Dogg) – ‘California Gurls’ (Prod. Dr. Luke, Benny Blanco)

- Usher (ft. will.i.am) – ‘OMG’ (Prod. will.i.am)

- B.o.B (ft. Hayley Williams) – ‘Airplanes’ (Prod. Alex Da Kid)

- Eminem (ft. Rihanna) – ‘Love the Way You Lie’ (Prod. Alex Da Kid)

- Lady Gaga – ‘Bad Romance’ (Prod. RedOne, Lady Gaga)

- Taio Cruz – ‘Dynamite’ (Prod. Dr. Luke, Benny Blanco)

- Taio Cruz (ft. Ludacris) – ‘Break Your Heart’ (Prod. Fraser T Smith)

Three of the top 10 songs (‘Tik Tok’, ‘California Gurls’ and ‘Dynamite’) were produced by chart-topper Dr. Luke. He produced multiple hits throughout the 2000s and by 2010, his signature ‘wall of sound’ production – with a heavy use of compression – was a textbook example of the ‘loudness wars’ era we’re still living in, where audio is pushed to the maximum volume limit at the expense of dynamic range. If you were to look at the waveforms of ‘Tik Tok’ or ‘Dynamite,’ they would look like solid rectangles (brickwalls). There is almost no difference in volume between the verses and the choruses.

The onset of the artificial

In each of those Top 10 records, you’ve also got huge amounts of auto-tune, the millennial ‘whoop’ and heavily side-chained kick drums and bass which creates that pumping sensation which feels more artificial than organic. This relentless onslaught of sound would lead to a rejection of such techniques by many producers.

A quick side-note, to appease the ‘we never stopped making it that way’-ers’, analog was not completely cast aside. There were plenty of DAWless luddites throughout the DAW days. The Blue Man Group have remained blue, weird and predominantly ever analog since 1987, they only use DAWs to connect their pipes and other strange sounds. In the Techno underground artists like KiNK were already famous for their massive, computer-free compositions and, of course, the old-school Hip-Hop heads (using the Akai MPC 2000XL or 3000) never fully entered the DAW world.

The resurgence

The analog resurgence didn’t happen overnight. It was a slow-burn revolution made possible by two things: passionate people and cheaper hardware. There’s too many to mention but some key releases of cheaper instruments included the Korg Monotron, the Arturia MiniBrute, Roland’s AIRA TR-8, Make Noise’s 0-Coast and Behringer’s Model D. The Eurorack style standardization of modular synth sizes, led by Dieter Doepfer. Compact all-in-one machines like the Elektron Digitakt, Teenage Engineering OP-1 and Novation Circuit.

Aphex Twin has always been an advocate for hardware and custom built circuits in music production. With the releases of albums Acoustica (2011) and Syro (2014), he reminded the world of the sonic weight of high-end analog, DAWless production. Acoustica’s sublime use of orchestral instruments was a stark contrast to the sound libraries making millions at the time. With Syro, the man also known as Richard James included a gear list in the liner notes, showcasing a massive array of hardware.

New platforms, new technology

Around the same time, Boiler Room sets from KiNK as well as Techno heavyweights Blawan and Pariah began to pop up on YouTube. As the influencer-era began to take shape in the 2010s, other interesting technology-bending individuals began to rise on the video platform where live-sets could be gawped at by young music fans all over the world. In my opinion, the raw personification of this is YouTuber, electronics enthusiast and musician, Look Mum No Computer (Sam Battle). He’s the tinkerer known for creating his own instruments out of anything he can get his hands on. In his time, he’s made a synthesiser with a Raleigh Chopper bicycle, a Gameboy triple oscillator synthesizer and my absolute favourite, the Furby choir organ.

The YouTubers Bo Beats & Sarah Belle Reid also helped demystify the world of modular synthesis and hardware workflow for the next generation. Then there’s the incredibly talented ancient technology advocate, German electronic music composer Henibach. Based in Berlin, he’s one of the most influential figures in the DAWless movement. Fuelled by what he calls “childlike wonder”, his approach to electronic music is a calming salve to the loudness of modern club music. He often explores the beauty of things breaking, magnetic tapes hissing, old circuits whining all whilst wearing cozy sweaters. He has an impressive YouTube archive from the last 13 years, exploring equipment and ambient sounds, making the analog world of music production that little less scary.

Just like old times

Today, more people than ever work at computers for their 9-to-5 jobs. DAWless production offers a way to make art without staring at the same blue-light interface. Artists like Overmono, Nala Sinephro and Alessandro Cortini of Nine Inch Nails are showing how new sounds can come from old hardware. Kevin Parker of Tame Impala (pictured above) is a fierce analog advocate, telling Synth History in 2023: “I love analog synths… It’s all about the process. The process of using an old synth just sort of makes you feel a certain way and that leads you to different things, for better or for worse.”

There’s even been a resurgence in old school DAWS like the type you’ll find on the Amiga 1200. One particular name that comes to mind is the one of a kind Jungle and Hip Hop producer Pete Cannon, who breaks down his old school methods on Youtube all the time.

The quest for simplicity

The DAWless movement is a rejection of the mass-produced commercial market sound and perfectionism. Many releases and live performances from the DAWless movement are improvised and magical. It’s a movement we’ll be closely listening out for via the Mixcloud tags #modularsynth and #analogelectronicmusic.

At a time when everyone seems to be doing everything all at once and, as electronic producers are trying to differentiate themselves from the many millions out there, the words of the mighty Hans Zimmer from a Reddit AMA might just point us in the right direction: “I’ve spent my life trying to make things simpler. Because I find that ultimately, complicated doesn’t reach the heart.”